Fertilizing Your Hibiscus In Winter

Knowing when to adjust the feeding and watering of your hibiscus is one of the most important skills a good grower needs to master. In many parts of Southern California, we are able to keep our favorite plants outside year-round thanks to the Pacific Ocean and its ability to moderate our annual temperatures.

Our plants can experience the changes in the seasons even when it doesn’t always feel like the seasons change a whole lot here. You would be surprised to see how much your hibiscus know what time of year it is and they will start to make changes, even when the weather and temperatures still seem to be perfect for them. We have observed every year in November that the blooms start to diminish in size and the splendid color displays of summer start become less intense. Don’t get discouraged! Some cultivars’ blooms look their best in cooler conditions — it just depends on which hibiscus plants you have.

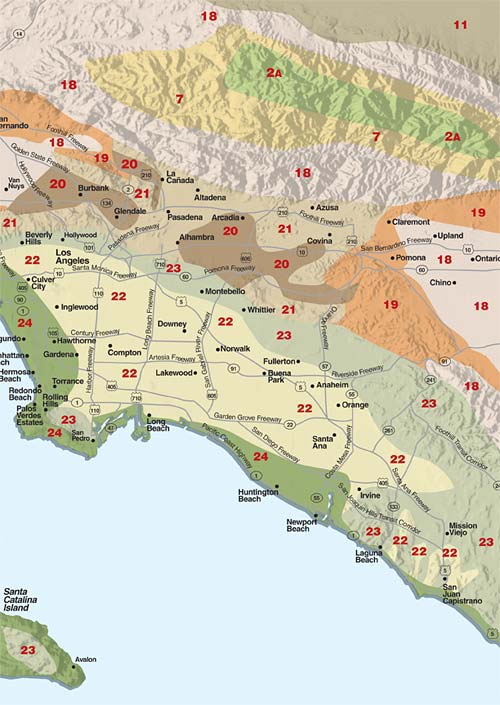

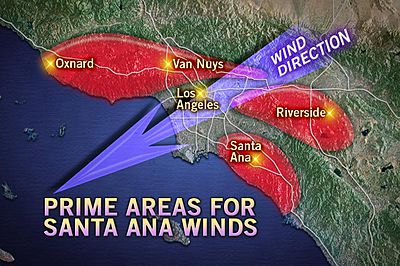

Before we get into what to do with fertilizing your plants in winter, let’s cover a few basics of taking care of your hibiscus in winter. The Pacific Ocean is the great moderator of our climate here in Southern California. As you get further inland from the ocean, that moderating effect diminishes and you become more vulnerable to the continental air masses of winter. If your average annual low temperatures gets near or below freezing on occasion during the cool months, your hibiscus need to be in pots and placed either inside or under a substantial protective covering at least during those stretches, if not for the entire cool months. Hibiscus are tropical plants and have no way to protect themselves from frost of freezing temperatures.

Another big problem for hibiscus is our cold and super dry wind events we get frequently from November thru March — The Santa Anas. Hibiscus are from the tropics and bred to live in constant warmth and high humidity year round. The wintertime Santa Ana wind events are the exact opposite of what they need. The worst case scenario is that the plants can become wind burned and quickly dry out. What compounds this situation is when their metabolism significantly slows down during this time they are very slow at getting nutrients and water back into all the branches and leaves. This may result in further plant decline to the point where it can go into catastrophic shock and either shut down, and go barren, or die. If you live inland and are prone to those cold and dry wind events, your hibiscus should be in pots and moved to a sheltered location away from the direct force of the winds. An example would be if the winds blow into the north side of your property, you would want to place your plants on the south side and up against something like your home that will shield them from the full force of the winds.

Another important basic is when you water your hibiscus, they should also be fed.

The only exception to this is when the temperatures are over 105°F and I will talk about this later on in this article. Hibiscus have tender root systems that are susceptible to root rot. Root rot happens when the soil your hibiscus is growing in becomes too saturated with water and there is not enough air left in it. Hibiscus originate from tropical volcanic climates where the soil is usually rocky and porous. Tropical climates usually mean intense rain for short periods of time. Hibiscus are used to a lot of water that quickly drains past its root system. The plant returns to a soil environment that has lots of air in it. The volcanic soil is full of minerals, such as iron and sulfur. Hibiscus have developed into plants that are dependent on a high and readily available amounts of nutrients for them to greedily uptake. For many of us here in Southern California, we have clay soils which are pretty much the opposite of the porous, volcanic soils. It is critical that if you grow your hibiscus in the ground you dig very large holes or trenches and replace the native soil with a soil mix that is heavy in perlite and/or pumice stone so that the roots of your plants have a very well-draining environment. We recommend to dig a hole at least 1 foot down and 1 foot in diameter around your plant, at a minimum. Shadier spots the holes should be larger, if you have the space to do so, to increase drainage and the area that water can disperse into.

Root rot is at its worst in the cooler months.

The pathogens that cause root rot flourish the most, and multiply the fastest, in an environment that has no oxygen and is cold. In wintertime your plants are most at risk for root rot but, ironically, we see many of our growers get root rot in the summer and fall. This may be surprising at first but the answer is simple: When the weather is hot and dry people tend to water their plants a lot at the first sign the soil looks dry. The soil looks dry at the surface but many times if you were to dig deep down to where the roots are, chances are it is still wet, if not very wet. Unknowingly, many growers add way too much water during those hot stretches. Instead of lightly watering the surface to keep that layer moist, they are saturating the soil deep down, eliminating the much needed air. A simple way to avoid this is to have a water meter that is long enough to probe all the way down to the bottom of your pots.

We recommend slowly probing into your soil, so you can watch your meter and see where the moisture level starts to change from the dry to moist. If you see that towards the bottom it is very wet, then you want to sprinkle just enough water on the soil to moisten that top layer only. You have to become an artist with a delicate and masterful touch!

Also remember root rot is an infection inside your plant. It is contagious, just like humans-spreading diseases. If you have a plant that has root rot or died of root rot, you need to disinfect your pot and any tools used handling them. Throw away all soil, too, as it is now full of the pathogens that infected your plant and will just reinfect any new healthy plants you replace it with. For existing plants you need to very gently bare root them and wash the roots with a 10% bleach solution, cutting off all rotted roots. Make sure to disinfect your sheers after each cut, as you can reinfect your plant. Once completed, repot in fresh soil after you have disinfected your pot. We recommend disinfecting your pots with pure bleach, so they will not retain any surviving pathogens.

Never rest easy when you think you have the right soil mix and a good draining pot. You will be amazed how quickly hibiscus roots will plug up all your drainage holes and, before you know it, you are getting root rot. An example on the extreme end is I have 9 gallon ceramic pots and I drilled 7-8 additional large holes on the bottom of my pots. I then added plastic furniture coasters on the bottom to raise the pots off the ground to ensure great drainage and lots of air circulating under the pot. Within 1 year, some of those plants started to get root rot. It turns out those extra vigorous Hidden Valley Hibiscus root systems had plugged up all the holes and that is in a 9 gallon pot! I suggest watching our video, by local grower Brad Daniels, on how to root prune. It is a skill and action all good hibiscus growers will need to learn and regularly do.

On to fertilizing your hibiscus in winter. The rest of the year, minus heat waves, just follow the instructions on the fertilizer label. We highly recommend using Hidden Valley Hibiscus Special Blend Fertilizer as it is formulated for exotic hibiscus. The suggested dose is one teaspoon per gallon of water.

You should always be feeding your exotic hibiscus year round. How much do you feed your exotic hibiscus during certain times of the year? This depends on the weather and temperature. Your plant absorbs nutrients and water based on the heat it is exposed to.

The hotter it gets the quicker, the hibiscus’ metabolism increases, and it will take in more water and nutrients. When temps get over 95°F you will have to start reducing the amount of fertilizer your plants get, since their metabolism is speeding up a lot. What was once fine for your plants might start to burn them, since they are up taking nutrients at a much faster rate. I start to reduce the amount of fertilizer by 1/4 for every 5 degrees over 95°F. If the temps get over 105°F, I don’t feed them any fertilizer and just give them water. That is very rare occurrence and might only happen a few days a year where I live. This is really the only time you will want to water your plants without feeding them.

For the colder months, your plant’s metabolism will slow down. I have observed, along with HVH, that the 50°F barrier seems to be a good indicator to watch for. Once night temperatures get under 50°F, you will see your plants start to really slow down. If the nightly temperatures get under 40°F, their metabolism will slow down almost to a crawl. The hibiscus are not up to taking much water or much fertilizer at this temperature. If you continue to feed them at regular amounts, like you would in spring and summer, those fertilizers start to build up in the soil of your plant’s rootball. This can lead to severe fertilizer burn when the plant goes back to its regular metabolism. I would advise you do the same thing as when it is hot and reduce the amounts of fertilizer.

What you see now happened 2-3 weeks ago. As the temperatures start to warm up from the winter lows, it will take your plants 2-3 weeks to start to rebound and speed up their metabolism. You need to be patient and wait for that lag time before you start to increase their fertilizer again. We advise keeping a log, journal, or some sort of tracking mechanism of the weather, tempertures and inputs you gave your hibiscus, so that you will best gauge when and how much to gradually increase the fertilizer for your plants.

Another important factor: When your plant’s metabolism slows down, it also takes longer for that lag time to pass. The colder the nights, the slower your plant becomes. It could take longer than the normal 2-3 weeks to see the change back to more normal metabolic rates. For instance, if the night time temps get into the mid 30°s that will slow your plant down to an extremely slow metabolic rate, to the point where it might take 4-5 weeks for it to rebound once the weather pattern finally shifts and warmer weather starts up again.

Getting under the 40°F marker is a good indicator to roughly mark when your plant’s metabolism will take longer than the usual 2-3 weeks of lag time to show effects. The same is true in summer but the opposite. When temps get over 100°F, the lag time is closer to 1-1.5 weeks. When over 105°F, it is around 5-7 days.

The last factor to keep in mind when feeding your plants in the cooler months is how wet the soil is. We have had quite a bit of rain the last several weeks. Though the night temperatures have only gotten down to the mid 40°Fs, I have not fed my plants for over 2 weeks, because the soil is way too wet. The hibiscus would like to be fed, but if I did that I would be placing too much water in already wet soil.

One positive effect from lots of rain is it will also wash down excess fertilizer past the rootball zone for in-ground plants. The rain also helps to wash off your plants, and all the dust and things that accumulate on them. If your plants are in a protected area from the rain than you’re good to feed them. Track the nightly low temperatures to know how much to feed them. Once the temps get under 50°F, you will want to start reducing the amount of fertilizer. I would use the same rule of thumb as for when it is hot. For every 5 degrees in decreasing temperature, reduce the amount you are feeding them by 1/4.

If you have any questions or comments please use our contact form here on our website.